Keita Takeuchi

In Scotland, damages on crops and forests have been growing severer, as excessive number of deer eat up pasture grass, wheat, rape seed and tree buds and shoots, and trample down plants growing in the forests. In an effort to manage deer which roam far and wide through the vast forests, stakeholders formed deer management groups and have succeeded in reducing the number of deer and damage on crops.

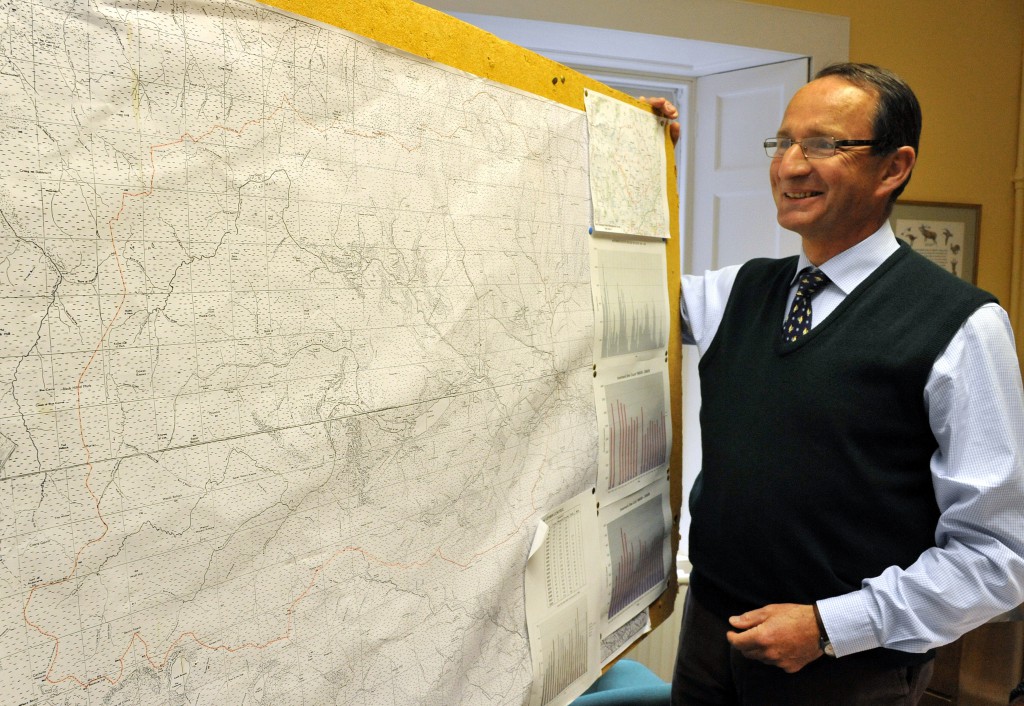

According to Richard Cooke, executive committee chairman of the Association of Deer Management Groups (ADMG), the groups have a tough task of handling conflicts of interests among different stakeholders. The association, based in the town of Brechin, is facing a number of challenges concerning appropriate management of deer, Cooke says.

In the 1970s and 80s, as a result of generally warm winters in Scotland, foliage remained in the forests even in winter and ample food led to an increase in the number of wild deer. The increase was also due to inappropriate deer management by landowners who enjoy hunting. The number of red deer, which has the largest population among deer species, was estimated to be roughly 150,000 in the 1960s in the area equivalent to that of Hokkaido, but it rose to as many as 450,000 in the late 1990s. Roe deer also increased, giving damage to farmlands adjacent to forests.

Kenny Willmitt, development officer of the British Association for Shooting and Conservation’s branch in Scotland, recalls that it was not uncommon for landowners, who come to their land only to hunt, to get into trouble with local farmers and residents.

To tackle problems related to deer management, the Deer (Scotland) Act was revised in 1996. Under the revised law, landowers, hunters, environmental groups and local residents should together establish a regional group which will be responsible for deer management. Roughly 60 groups have been engaged in deer management activities in rural areas across Scotland, and managed to reduce the number of red deer to around 380,000 in 2010.

Every year, each group creates management plans based on the estimated number of deer and a distribution map, and determines the biologically appropriate number of deer for each habitat. They often face conflicts of interests in the process of forming plans. According to Alastair MacGugan, wildlife management manager at the government-funded Scottish Natural Heritage which supports the creation of the plan, landowners and hunters state that the number of deer should be 12 per square kilometer, while those working for plant protection insist on four or less.

Usually, it is the group chairman who leads the group to reach consensus, but if they fail to strike a deal, the ADMG will mediate, and if that fails as well, the issue will be handled under the Scottish Natural Heritage’s dispute settlement arrangements. The SNH’s decision has a binding force under the Deer Act, and has worked effectively in compiling management plans.

Activities under deer management groups contributed to facilitating exchange between different parties, revitalizing the local economy as a result. Proper management of forests led to increasing popularity of outdoor recreation such as hunting tours, trekking and fishing, leading to more employment opportunities for young people who work as groundskeepers and mountain guides. The economic benefits of the activities are estimated to total 240 million pounds (roughly JPY 37.7 billion) yearly for the whole of Scotland. MacGugan said appropriate management activities also helped reduce crop damages caused by wildlife.

Cooke said members of the management groups share the view that new benefits can be created if different parties get involved in deer management, adding that deer are everybody’s asset, not a nuisance.

Richard Cooke, chairman of the Association of Deer Management Groups, stands before a deer distribution map at the association office in Brechin, Scotland.

(Oct. 19, 2013)